Multi-media Essay 1

Tamaruis Toles

Dr. Robles

CODES 120: Research Team

September 16th 2025

From Silence to Captain

Cheerleading has always been more than a sport for me, to be honest I look at it like it’s a system that shaped my confidence, my identity, and the way I was seen by others. But my experience was not the same everywhere. When I cheered at North Point High School, I felt invisible. I faced micro aggressions about my hair, my body, and my culture. I was never fully recognized for my potential, no matter how much effort I put in. The environment was mostly white, guided by Universal Cheerleaders Association (UCA) standards that valued a certain “look” and “style” of cheer that never included me.

Later, when I transferred to Riverview, I stepped into a completely different system. There, I could wear ethnic hairstyles without judgment. I was encouraged to bring my full self. I even became varsity cheer captain. The contrast between these two systems exposed something much bigger than just cheer.. it revealed how race, culture, and institutional power shape opportunities, identity, and leadership.

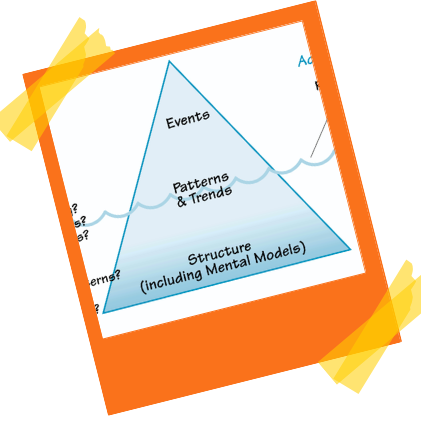

In this essay, I’ll use systems thinking to tell this story. I’ll talk about the events I experienced, the patterns that kept repeating, and the structures underneath that shaped them. And by looking below the surface, like the iceberg model in Stroh’s Systems Thinking for Social Change. I’ll show how racism in cheer is not just about one bad comment but about a system designed to reward certain people and exclude others.

At North Point, the first thing I noticed was how my hair was always a topic of conversation. If I wore braids, it was “too distracting.” If I wore my natural curls, I was told it didn’t “match the team look.” Meanwhile, white teammates could dye their hair bright colors or wear extensions, and nobody said a word.

One moment stands out clearly: we had a competition, and I had practiced harder than ever before. My stunts were clean, my jumps were sharp, but when it came time to decide who was front and center, I was overlooked. A coach said, “We just want a uniform look.” That phrase stuck with me, it wasn’t about skill, it was about fitting a narrow image of what cheer should look like.

These weren’t accidents. They were events shaped by the system. Each microaggression may have seemed small, but together they built an environment where I felt erased.

Looking back, I see patterns that repeated. At North Point, leadership roles always went to white girls. They were more likely to be chosen for center spots, to be “flyers,” and to get recognized in pep rallies. Meanwhile, Black cheerleaders were often placed in the back or given base roles.

Another pattern was the policing of appearance. Hairstyles, nails, even the way we spoke were judged. “Professional” and “clean” became code words for “white.” Over time, I noticed that Black cheerleaders either quit, were pushed out, or just stayed quiet to survive.

By contrast, Riverview flipped the script. There, individuality was celebrated. Braids, beads, and natural hair weren’t just allowed, they were seen as part of the culture. The team recognized skill over appearance, and that’s why I rose to varsity captain. The pattern at Riverview was empowerment, while the pattern at North Point was suppression.

Systems thinking pushes us to ask: what structures created these differences? Why was North Point so different from Riverview?

At North Point, the system was shaped by UCA’s influence. UCA cheer has its roots in white Southern traditions. It values precision, uniformity, and a certain “aesthetic” that often aligns with whiteness. The variables at play included:

- Power dynamics: Coaches (mostly white) decided what “looked right.”

- Policies: Strict appearance rules discouraged cultural expression.

- Perceptions: Cheer was seen as a performance for the school’s image, not as self, expression.

These variables reinforced each other. The more coaches pushed uniformity, the more Black cheerleaders felt excluded. Over time, that led to fewer Black leaders in the program, which then reinforced the idea that cheer was “not for us.”

At Riverview, the system worked differently. The coaches reflected the community. The policy was flexibility, not control. The power dynamic was shared, students had a voice. And the perception of cheer was community pride, not just performance. That’s why I could thrive.

The deepest part of the iceberg is mental models, the beliefs people hold, often without realizing it. At North Point, the mental model was: “Cheer should look one way, and that way is white.” Even when nobody said it outright, it showed up in decisions.

At Riverview, the mental model was: “Cheer is about skill, leadership, and pride in who you are.” That belief shaped every choice coaches and teammates made.

Changing mental models is the hardest part of systems change. But it’s also the most powerful.

When I think about my journey, I see how systems can silence or amplify people. At North Point, I felt small, like my voice didn’t matter. But Riverview gave me space to grow. Becoming varsity captain wasn’t just about leading cheers, it was about finally being seen.

This transformation taught me two lessons. First, representation matters. Having leaders and coaches who understand you changes everything. Second, systems don’t just happen; they’re built. If a system can exclude, it can also be rebuilt to include.

My story isn’t just about me. It’s about how schools, teams, and organizations can either reproduce racism or resist it. Cheer may seem like pom, poms and pep rallies, but it’s a mirror of society. At North Point, the mirror showed exclusion. At Riverview, it reflected empowerment.

By using systems thinking, I’ve learned to look beneath the surface. It’s not just about one coach or one hairstyle every choice coach and teammate of who holds power, what rules exist, and what people believe.

If we want to change these systems, we have to challenge the mental models at the bottom of the iceberg. For me, that means speaking up, telling my story, and reminding others that Black girls belong in cheer,not just in the back, but front and center.